Working with Decision Makers in the Internal Ecosystem

The internal ecosystem of an institution is comprised of a range of stakeholders including:

-

the director of the institution;

-

the staff and caregivers of the institution;

-

children and families;

-

partner charities and organizations supporting the institution;

-

individual donors supporting the institution;

-

and the original founder of the institution.

-

In some cases, the founder may also be the director or principal donor, or sometimes both.

-

In other cases, the founder may have stepped out of an active role with the institution and has limited or no involvement.

-

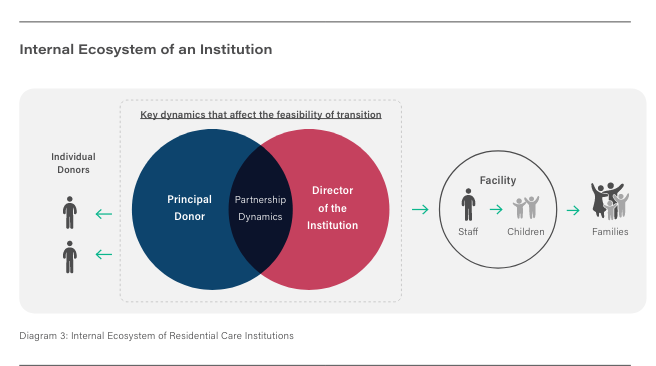

In this ecosystem, all of these stakeholders have an important role and need to be onboarded to ensure an effective transition. However, the two key stakeholders who exert the most significant influence on organizational decision- making and therefore the process of transition are:

-

The director, who has operational control over the institution, including staff and caregivers;

- and The principal donor, the person who represents the main or largest donor, or primary fundraiser. The principal donor, the person who represents the main or largest donor, or primary fundraiser. The principal donor:

- can be an individual or entity;

- typically represents a charity, organization, church, family trust, or business that is funding the institution;

- often collects donations from individual donors and is the channel through which individual donations flow to the institution;

- typically manages the communication with individual donors; and

- in rarer cases, financially supports the institution independently.

In some cases, the founder of the institution may have transitioned from the role of director into the role of principal donor.

Origins of the Tool

This tool evolved from the learning and experience of the authors throughout their work to transition privately-run and funded institutions in various countries and regions. Over time, the authors observed trends and key indicators that enabled them to anticipate how a transition might unfold.

These trends and key indicators often stemmed from dynamics linked to the motivations and characteristics of the director and principal donor of an institution, and the relationship and history between them. These dynamics created the ‘starting point’, or in other words, the enabling environment. By analyzing the enabling environment, the authors found that they could anticipate the potential path of a transition and use these insights to develop the safest and most effective strategy possible. The documentation of these learnings and trends spanning many years led to the development of this tool.

Acknowledgments

Reference Group

We wish to thank the practitioners and their respective organizations who participated in the reference group and contributed towards the development of the tool. The insights, experiences, learnings, and suggestions shared with us have been critical in ensuring its relevance to a diverse range of contexts.

Reference Group Members

| Andrea Nave | Forget Me Not Australia |

| Anju Pun | Forget Me Not Nepal |

| Beth Bradford | Changing the Way We Care |

| Daniel Nyan | Global Child Advocates |

| Dy Noeut | Children in Families Cambodia |

| Elli Oswald | Faith to Action |

| Gabriel Walder | Alliance for Children Everywhere |

| Jo Wakia | Maestral/Changing the Way We Care |

| Joseph Sentongo | CCCU Uganda |

| Katie Blok | ACC International Relief/Kinnected |

| Kristi Gleeson | Bethany Christian Services |

| Mara Cavanagh | Lumos |

| Michelle Grant | Accredited Mental Health Social Worker |

| Manan Naw Jar | Kinnected Myanmar |

| Niyoshi Metha | Miracle Foundation India |

| Peter Kamau | Child in Family Focus Kenya |

| Stephen Servant | Heaven’s Family US |

| Sully S.de Ucles | Maestral Guatemala |

| Robbie Wilson | Lumos |

We especially wish to thank Alliance for Children Everywhere and ACC International for testing the tool amongst their team and providing further feedback on usability. This helped us shape not only the structure but language of the tool to ensure its accessibility to a wide range of practitioners.

We also wish to express gratitude to Changing the Way We Care and USAID for supporting the development of this resource.

Background

Care Reforms: The Big Picture

The detriments of institutional care on children’s development and wellbeing are well-documented and well-established. The overwhelming evidence has led to a global call to end the institutionalization of children and has catalyzed child protection and care systems reforms in many regions and countries.

Care reforms are complex and entail multi-faceted changes at the systems level. They involve changes made to legislation, regulation, policy, services, resource allocation, and workforce training, as well as the development of new mechanisms for implementation and monitoring. They are government-led and often supported by inter-governmental and non-government agencies.

In countries where there is an over-reliance on institutional care, a key goal of reform efforts is to reorient the care systems towards family-based solutions, recognizing:

a. the family as the optimal environment for children’s development and wellbeing;

b. the right of the child to family-life;

c. the obligations of States to provide support to parents to fulfil their caregiving responsibilities towards children; and

d. the priority given to family-based alternative care in international norms.

This type of reform is referred to as ‘deinstitutionalization’ and includes efforts to reduce the number of children in institutions through reintegration and scaling back the number of institutions in operation, ideally through transition rather than closure. Transition is therefore a component of care reforms and should, to the extent possible, be linked to broader systems-level reforms, take place with involvement from the mandated authorities, and use established national procedures where they exist.

Transitional as the Ideal

Transition, as the name suggests, involves changing an organization's model of care or services from institutional to non-institutional ones. Transition, rather than closure, is ideal as it serves two purposes. Firstly, it contributes to the decrease in the number of institutions. Secondly, it allows new services to be developed that support children to remain in families. This happens when human, financial, and material resources used to sustain the institution are redirected and repurposed. Therefore, transition aims to shift resources away from institutional models but retain investment in child and family welfare systems.

Some organizations transition into programs that are set up to support the children reintegrating out of the transitioning institution. In other cases, new programs are developed to address a gap in the overall system that will continue to result in children being placed in institutions unless addressed. New programs do not have to be limited to alternative care services, such as foster care and kinship care. They can include programs related to education, disability, daycare, child-centered community development, or positive parenting. These programs all contribute to efforts to strengthen systems such as social protection, education, child welfare, or child protection, all of which will impact children’s care.

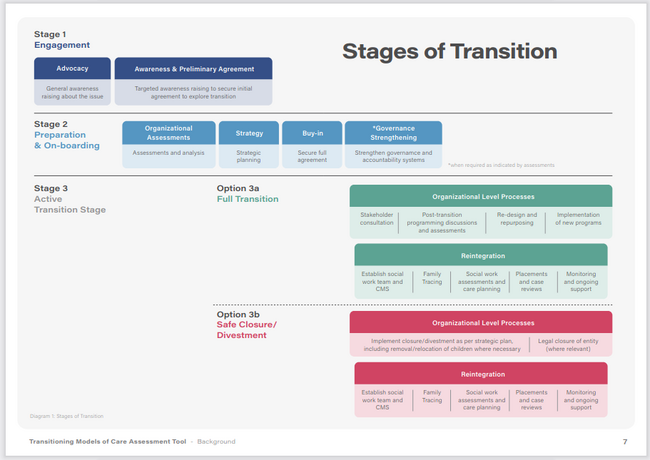

What Does Transition Involve?

Many people view transition of an institution as the same or similar to the reintegration process of children. While reintegration is one of the most important outcomes, transition is a much broader process. It involves change at every tier of the organization running the institution. This includes structural, policy, procedural, programmatic, and resourcing levels. As outlined in the diagram below, there are many stages and steps that need to take place before reintegration begins. Overlooking these critical stages can negatively impact the entire transition process and outcomes for the children. Transition strategies should be tailored to each organization, taking into account their unique starting point. If they begin by lacking sufficient structure or reporting procedures, strategies may need to address this to manage the change process, mitigate risk, or respond to any incidents that may emerge during transition.

Degrees of Success

There are a number of key outcomes associated with transitioning an institution, all of which contribute towards systems level care reform.

| Institution Level Outcomes | Systems Level Outcomes |

| Safe reintegration of children in the institution back into families and communities | Reduction in the overall number of children in institutional care |

| Divestment of human, financial, and material resources from an individual institution | Reduction in the overall number of institutions in operation |

| Reinvestment of human, financial, and material resources in family strengthening services or family-based alternative care | Development of non-institutional services as alternatives |

In an ideal transition scenario, all three of the institution level outcomes would be fully achieved, resulting in a full repurposing of the former institution, including all of its staff and resources. However, this is not always possible. There are some situations in which full transition is not the appropriate goal and could even place children at risk of harm. This is particularly the case where there is insufficient commitment to delivering high quality services, serious capacity or child protection related concerns, or mixed motives revealed in the assessment. These types of concerns may call into question the suitability of the directors, staff, or other stakeholders working directly with vulnerable children. In such instances, a more appropriate goal might be safe closure. This can be voluntary or enforced by the relevant authorities in more serious cases or as part of national efforts to scale back institutional care in the country. Depending on the context and nature of concerns, it may be entirely appropriate for directors and staff to transition into non-child welfare related projects.

While safe closure of an institution may not be the ideal or best-case scenario, it is a valid outcome and should not be perceived as failure. This is because safe closures still make important contributions to the systems level reform including the following outcomes:

- a reduction in the overall number of children in institutional care through safe reintegration; and

- a reduction in the overall number of institutions in operation through safe closure.

In some cases, a safe closure may also achieve the desired goal of reinvesting financial resources in non-institutional care services in a slightly different way. Donors who supported the institution undergoing closure can be encouraged and supported to reinvest their finances in other organizations running family strengthening services or family-based alternative care. This allows for the scaling up of existing alternatives run by organizations with demonstrated capacity and expertise.

Therefore, it is important to view success in transition work as inclusive of a continuum of outcomes and impacts, which all must be achieved in a manner that is safe and in the best interests of children. A realistic framing of success from the outset will enable practitioners to develop appropriate monitoring and evaluation frameworks. It is also critical to sustaining motivation and dedication in the face of complex and challenging work.

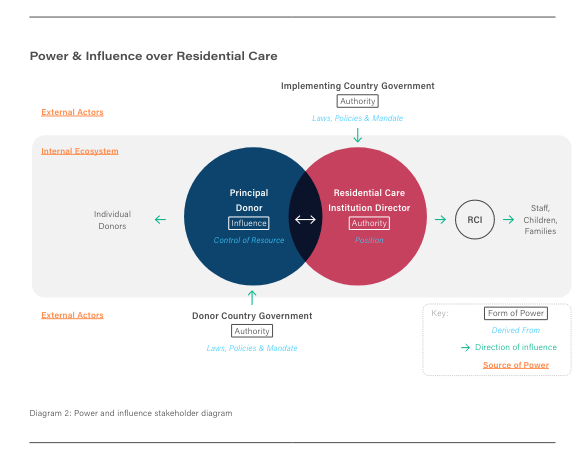

Power and its Impact on the Decision to Transition

In order to effectively outwork the transition of an institution, it is necessary to understand the power dynamics between the key stakeholders and work strategically with this knowledge. Power takes different forms and comes from various sources. When it comes to decision-making, including the decision to transition, power is typically held by three key stakeholders:

- Government

- Director

- Principal Donor

Governments in both donor and implementing countries exert different levels of power and influence on a transition. This is based on the strength and effectiveness of existing laws, policies, regulation, inspectorates, and child protection response mechanisms.

This is not only true of governments in countries where the institutions are operating. It is also true of governments in donor countries whose laws and regulations impact charities’ operations and fundraising efforts. In some cases, this includes regulations around funding or operating overseas institutions.

Having well-established and resourced government systems in countries where the institutions are run can certainly make it much easier to implement a transition and provides critical government support should issues arise. It can also result in government-mandated transitions or closures, which lends full government authority to the process. In many contexts where reforms are underway, relevant laws and policies often exist.

However, government resources are limited, and systems are in the early stages of development. This reduces the likelihood of transitions being enforced by government mandates or power. In these situations, it becomes even more critical to tap into the influence and power structures within the internal ecosystem of a given institution, both regarding buy-in and the development of a transition strategy.