Useful Resources and Tools | Case Studies | Tool Overview

Useful Resources and Tools

For an extensive list of resources visit:

Alternative Care Guidelines:

- Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children

UN General Assembly - Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children

Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland (CELCIS)

Reintegration Resources:

- A Continuum of Care for Orphans and Vulnerable Children

Faith to Action - Case Studies and Stories of Transitioning to Family Care

Faith to Action - Exploring Economic Strengthening within Family Reintegration

Retrak - Guidelines on Children’s Reintegration

Inter-agency group on children’s reintegration - Emily Delap and Joanna Wedge - Reaching for Home: Global learning on family reintegration in low and lower-middle income countries

Joanna Wedge, Abby Krumholz and Lindsay Jones - Reintegration Guidelines for Trafficked and Displaced Children Living in Institutions

Next Generation Nepal - Retrak: Standard Operating Procedures-Family Reintegration

Retrak - Toolkit for Practitioners

Better Care Network - Transitioning to Family Care for Children: A Guidance Manual

Faith to Action

Care Leaver Support Resources

- The Care Leaver Experience: A Report on Children and Young People’s Experiences in and After Leaving Residential Care in Uganda

Ismael Ddumba-Nyanzi, Melissa Fricke, Angie Hong Max, Mai Nambooze, Mark Riley - Uganda Care Leavers Project - Kenyan Care Leavers Resources

Kenyan Society for Care Leavers (KESCA) - Webinar: More Than Our Stories: Strategies for how to meaningfully engage care leavers in care reform

Better Care Network

Video Resources

- BCN Practitioner Videos

Better Care Network - Kinnected Myanmar- Hani and Thari Case Study

ACCI Relief - Kinnected Profile: Interview with Ou

ACCI Relief - Radical Change for the Love of Children Documentary

Orphan’s Tear Ministry

Tools and Templates

- Care Leaver Support Program MoU Template

Kinnected Myanmar - Institution Minimum Standards Assessment Tool

ACC International Relief - Partnership Agreement Template

Kinnected Myanmar - Partnership Due Diligence Assessment Tool

Rethink Orphanages

Spanish Resources

Case Studies

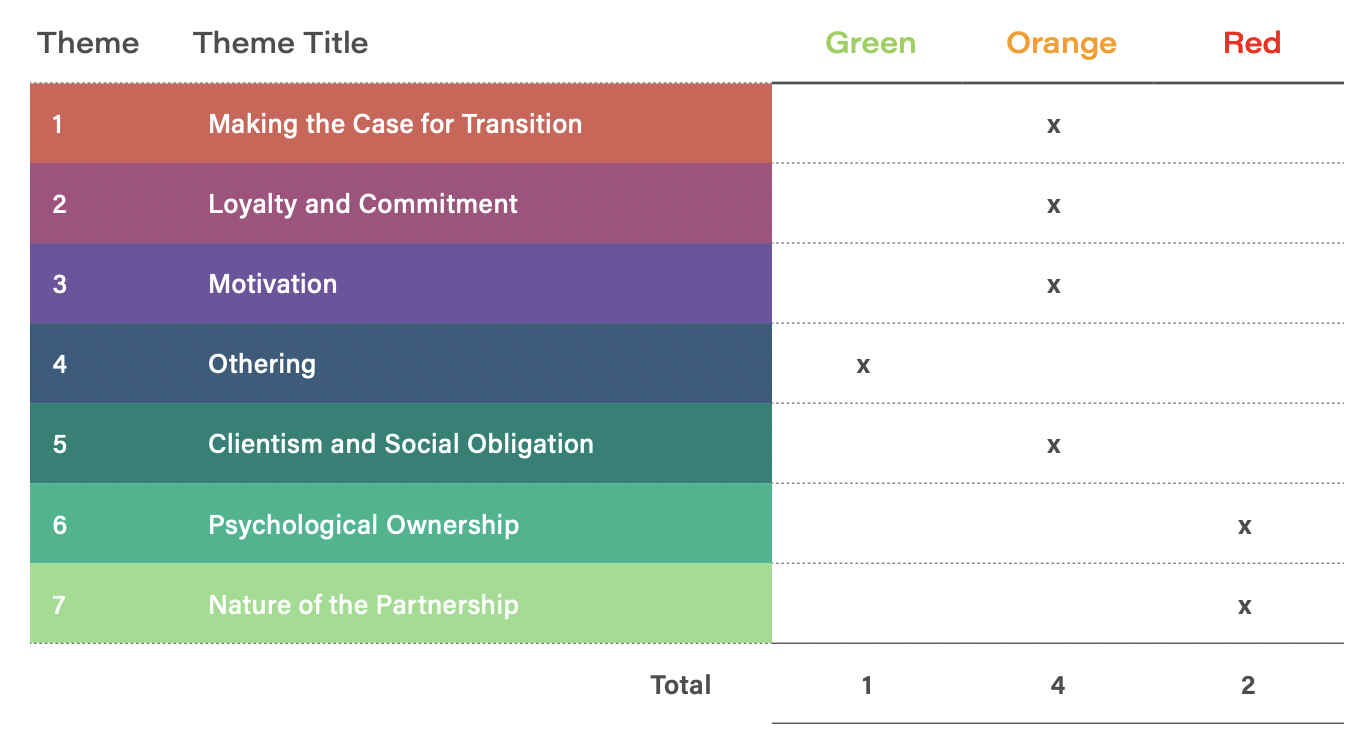

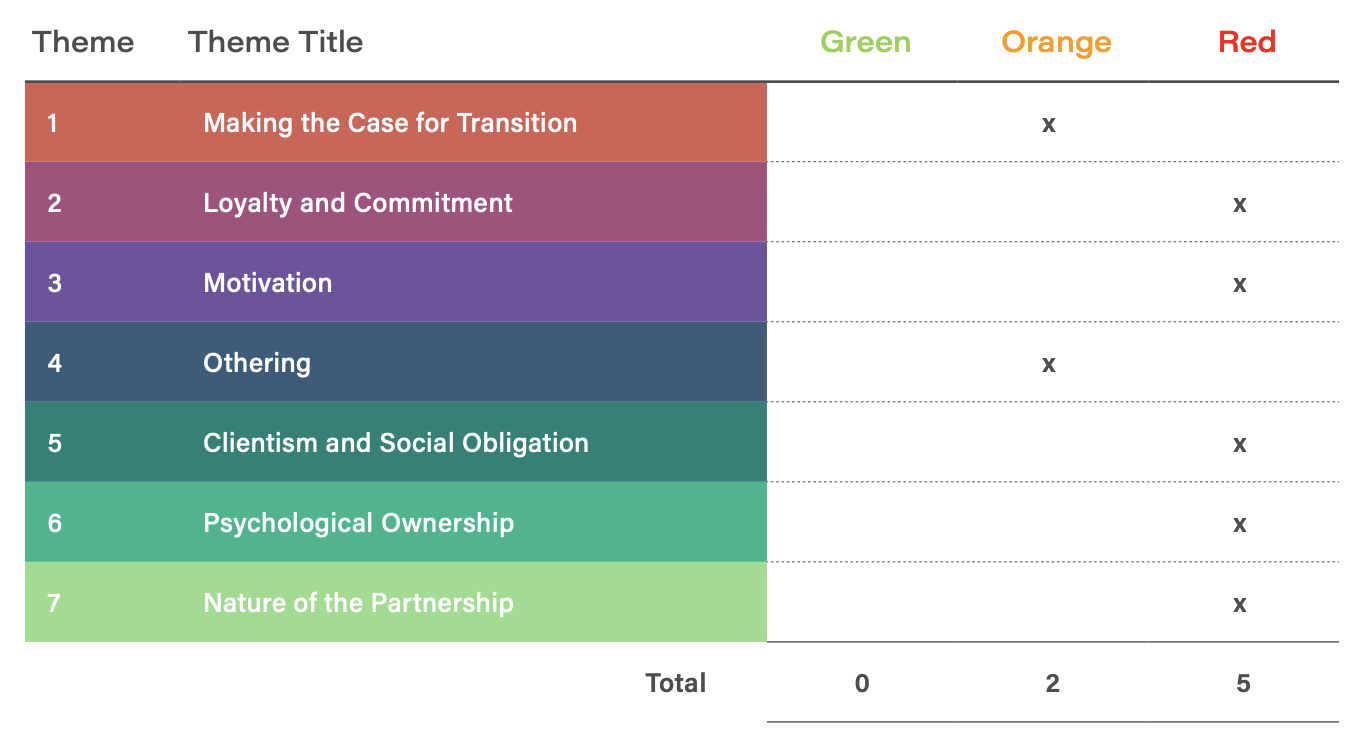

The following section contains the three case studies that are referenced throughout the tool. These have been included as concrete examples to make the tool more practical and accessible. Each case study is a summary of a real transition which has been fully anonymized. The case studies have been categorized by their final ratings: green, orange, and red. The table at the end of each case study contains the overall scoring and a summary of the implications, outlining the indicators that led to the scoring as well as the interventions undertaken by practitioners in response.

All of the indicators have been extracted from these case studies and listed in the tables under each theme in the body of the tool. All identifying information, including the names of people, organizations, and locations, have been changed or omitted to maintain anonymity and to respect the privacy of those involved. All names were randomly selected or created, and any similarities to exisiting organizational names or individuals are purely coincidental.

CASE STUDY: BRIDGES SAFEHOUSE

(Spanish version)

From its inception, Bridges had always prioritized family care for the children who came through their facility and never accepted children for the purpose of providing access to better education. However, the children and families they worked with faced a slew of complex challenges stemming from their migration out of a bordering country to escape armed conflict. They were often denied their basic human rights and struggled with cyclical poverty, incarceration, drug trafficking, and abuse.

Several years later, Bridges had established three more facilities for children and families from these various high-risk target groups, one of which provided temporary shelter to mothers and their children coming out of domestic violence situations. Although they reintegrated nearly 200 children out of their facilities over time, they were constantly taking in new referrals from the government, child protection networks, their crisis hotline, and community members. Some of the key Bridges staff members knew that there had to be better alternatives to continuing to take in more placements but did not know how or where to begin.

Although Thomas had been living in the country for more than ten years, spoke the language, and had friendships with members of the local community, he came to recognize his own limitations as an expatriate founder and pushed for a shift to national leadership. He appointed Bridges’ community outreach team leader, Kamal, with oversight of the project and its four facilities, promoting him into the role of director of the organization. At the same time, Thomas also stepped out of his role as principal donor, appointing Nina, an expatriate staff member with a social work background, to the task of overseeing the overseas funding organization as executive director.

Thus two staff members with relevant experience and professional backgrounds were entrusted with the responsibility of making organizational and programmatic decisions. Kamal, as the new director, was given the space to shape the project relying on his professional training in community development, as well as his personal experience as a member of the migrant community he served. Nina, in her new role as principal donor, worked to strengthen their organizational practices and financial transparency.

Armed with a skill set unusual for most principal donors, Nina was also able to utilize her relevant professional qualifications, two years of on-the-ground experience working directly with families, and near-fluency in the migrant community language, in her fundraising responsibilities. She effectively communicated complex messaging to her donor base around the root causes Bridges was seeking to address through their work and developed ethical fundraising strategies without relying on the ubiquitous and problematic ‘orphan care’ messaging.

Kamal turned his attention to advocacy within government and community groups and ramped up their existing efforts to prevent family separation. While their prevention work with families proved largely successful, their search for family-based care alternatives in the community proved less so. When Kamal eventually came into contact with Child and Family Development Agency, an external organization providing technical support for the transition out of institutional care, he was finally able to access the guidance and tools he needed to make progress towards the development of formal foster care in the community.

Child and Family Development Agency connected Kamal to other practitioners in the region who were already implementing foster care despite their initial doubts that it could be possible. Kamal now credits one of the workshops he attended through these connections as pivotal in his decision to fully transition out of residential care. Although he was already familiar with the evidence on the harmful effects of institutional care, and even provided training to government officials on the subject, there had been a disconnect in how such evidence related to their own residential facilities.

Through nuanced discussions with Child and Family Development Agency that challenged some of the views Kamal did not realize he held, he came to identify behaviors of institutionalized children in some of the children in their care. Kamal was also provided with technical guidance around the implementation of foster care within contexts with weak regulatory frameworks. This included the development of screening, recruitment, and training strategies as well as concrete explorations of how to navigate the complex dynamics of securing government approval for foster care of undocumented children. Through the combination of these various types of support and connection to peer practitioners, Kamal was able to visualize how transitioning out of a residential care model was relevant and tangible for Bridges, and it was only then that transition became a reality they could pursue.

Kamal’s final moment of clarity came during a farewell event Bridges organized for some of the children leaving their facilities to return to their parents. As everyone grew emotional at the prospect of the children’s permanent departure, Kamal was shocked to hear other children asking him in tears when it would be their turn to go home. Throughout ensuing conversations with the children, Kamal heard directly from them about their desire to live with their families, even in cases where there had been history of severe abuse.

Kamal’s initial motivation to work for an organization supporting at-risk children transformed into a personal responsibility to see the children safely back into their families and communities where they longed to be. During future farewell events for other children leaving their facilities, he felt hugely burdened thinking about the impact of those events on the remaining children, as they waited for their turn to go home.

Through a formal partnership signed with Child and Family Development Agency in 2014, Bridges spent the following two years preparing for a full transition out of residential care. They worked through advocacy and partnerships to secure government permission for a foster care pilot and improved their reintegration practices utilizing more technically robust procedures and interventions. Nina continued to lead Bridges through an involved process of implementing changes at the organizational level.

Although Bridges and its governing and funding boards were legally registered, the partnership with the principal donor organization had previously been based primarily on trust. There were few written agreements or frameworks in place outlining clear expectations around the use of funds, reporting requirements, programmatic activities and budgets, and any breaches of policy. Through Nina’s work with the overseas funding board and reporting templates provided by Child and Family Development Agency, the formerly loose partnership structure was strengthened into a formal and contractual partnership meeting the necessary due diligence requirements.

Despite what looked to be a smooth transition ahead, Thomas, the founder and former director/principal donor unexpectedly re-entered the picture partway through the process, imposing an unrealistic deadline of six months for the closure of all four of their facilities. Kamal requested the support of an overseas practitioner with foster care experience who had had some previous involvement with Bridges, and Nina was able to secure funding for an extended in-country placement for the practitioner to work alongside Thomas and the rest of the team. Transition work continued throughout a highly stressful period that ultimately resulted in parting ways with Thomas, and Kamal recognizes now that he could not have survived the turbulent transition process without the ongoing support and guidance from both the practitioner and Nina.

By 2017, Bridges had closed three of their facilities and transformed the fourth one into a long-term small group home for children who could not be placed in families or communities. Nearly half of the children in their care at the start of the transition have now been placed into foster care and roughly the same number have been reintegrated into birth families and kinship care. The remaining young people are living in community-based care in semi-independent living arrangements with intensive support from social workers, and three children live in the small group home as they await foster care placements.

Kamal now delivers awareness raising workshops on family-based care, both within the migrant community as well as in his community of origin to prevent the flow of children from his home country into institutional care. Having experienced a full transition process and witnessed positive changes for many children he thought could never go home, he is more passionate than ever about supporting children to grow up in families and plans to support other institutions through the transition process.

SCORING

RATIONALE FOR SCORING AND TRANSITION STRATEGY

All of the individuals involved in the establishment, funding, and operations of the organization were motivated by a genuine and cause-based concern for children, and there was an absence of other motivations conflicting with the best interests of children. The director and principal donor were not the founders of the organization and instead were both employed and appointed to their positions. Their professional backgrounds contributed to their ability to theoretically understand the harmful effects and limitations of institutional care.

However, full buy-in was not achieved until, through an emotional experience of hearing directly from the children, the director made the connection between his theoretical understanding and how the evidence was apparent within his own facilities. Transition also did not seem feasible to the director until he was provided with technical support outlining concrete pathways to transition.

Intercultural dynamics and potential complications resulting from operation within a patronage system did not significantly impact the transition because the process was largely outworked by a director operating within his own community. He was hired into his position because of his qualifications and experience, rather than his relational connections to the community where the children originated.

Many of the common risks stemming from a loosely-structured partnership between the director and principal donor were curtailed by putting the appropriate frameworks and formal agreements in place. Any potential damage and interference caused by the founder, who no longer held influence tied to his former roles as director and principal donor, was severely limited by the restriction of his power and authority.

While it is not typical for transition projects to provide family-based alternative care as part of their post-transition programming, a number of factors made it possible for this organization. This included the absence of any concerning motives of either stakeholder, both stakeholders having relevant professional experience, a director who was a member of their target community and a principal donor who was well integrated into it, and a contractual partnership that was established well before the transition commenced.

However, the most significant factor was that they had already been providing similar services around reintegration and support for family-based care prior to transition. Although a handful of children who could not be placed in families or communities remained in their care for several years, the vast majority of children that came through their facilities were only in care between three to six months prior to reintegration. They had never solicited funding through misleading messages around ‘orphans’ or referred to the children as ‘theirs’, instead focusing on the importance of reunifying children with their families whenever possible.

Thus from an organizational, programmatic, and funding perspective, the organization did not have to undertake radical changes to continue to outwork family-based alternative care as part of their post-transition programming. This sets them apart from the majority of other transition projects where the provision of alternative care is feasible only under a carefully considered set of circumstances.

CASE STUDY: FIREFLY ORPHANAGE

(Spanish version)

While visiting overseas for an international conference, a UK-based non-profit organization called Together for Change came into contact with the director of an institution housing children who had reportedly lost their parents. Together for Change made the decision to financially support the institution and soon became its principal donor. The director of the institution went on to broker funding for dozens of other institutions within his extensive network, and over the next decade, Together for Change transferred the equivalent of more than 1 million US dollars into the director’s personal bank account. Amidst growing evidence of widespread financial misappropriation at the hands of many of the institution directors they had been supporting, Together for Change gradually came to discover that the director had authorized himself to take a 10% commission of all of the funds they had transferred.

While visiting overseas for an international conference, a UK-based non-profit organization called Together for Change came into contact with the director of an institution housing children who had reportedly lost their parents. Together for Change made the decision to financially support the institution and soon became its principal donor. The director of the institution went on to broker funding for dozens of other institutions within his extensive network, and over the next decade, Together for Change transferred the equivalent of more than 1 million US dollars into the director’s personal bank account. Amidst growing evidence of widespread financial misappropriation at the hands of many of the institution directors they had been supporting, Together for Change gradually came to discover that the director had authorized himself to take a 10% commission of all of the funds they had transferred.

Following the termination of their relationship with the institution director, Together for Change employed another director, Ethan, whom they had long supported and trusted. Ethan had earned overseas university-level qualifications and established Firefly Orphanage upon returning to his home country. As institutional care was the most common form of support for vulnerable children in his community, and many of his extended family members also operated institutions that were funded by Together for Change, it was for these reasons that Ethan came to establish his own institution.

While Ethan had a genuine concern for children and believed that he could improve their lives by providing them with access to higher quality education in the capital city, his decision to become involved in institutional care also stemmed from the knowledge that he could sustain his livelihood from it. Thus while the connection to institutional care was made via a relationship, his decision to become involved in institutional care was a rational one, not an emotional one.

In addition, as he commanded respect from his community from having obtained tertiary education qualifications overseas and having connections to foreign funding through Together for Change, the recruitment of children from his home village into Firefly established his role as patron to the families of those children. The resulting status and identity around his position as patron would later complicate efforts by social workers to reintegrate children out of Firefly and into his home community.

Aside from operating Firefly, Ethan’s newly assigned responsibilities included oversight of all of Together for Change’s partner institutions and disbursing monthly funds for their operations. Ethan was also tasked with assisting Together for Change in collecting photographs and information on all of the children in their partner institutions. As the child sponsorship model was Together for Change’s primary means of fundraising from their individual donors, they requested details about the personal histories of the children and the directors supplied them, both sides unaware of the special rights of protection entitled to children living outside of parental care.

During this period, Together for Change came into contact with an international training organization that delivered workshops raising awareness of the over-reliance on institutional care in lower-income countries. Excited by the prospect of a different solution for the children they had been supporting, Together for Change arranged for the training organization to deliver a mandatory workshop for all of their partner institution directors to learn about the harms of institutional care. Following the workshop, Together for Change strongly encouraged their partner institutions to pursue family-based care and transition their programs into non-institutional models. When the workshop and subsequent directive to transition did not result in any change or action by the institution directors, however, Together for Change sought and secured a partnership with Project Families, an organization providing technical support to those seeking to transition their partner institutions away from residential care.

After a period of strengthening Together for Change’s organizational policies and drafting written agreements outlining partnership standards, Project Families launched a series of monthly working groups for the institution directors. The following twelve months entailed frequent and extensive meetings dispelling common misconceptions about reintegration, discussing realistic ways to uphold child rights in a context with weak regulatory systems and few resources, and concretely mapping out a range of programmatic areas in which directors could continue to serve children post-transition.

While the majority chose not to pursue transition and a few were categorized as warranting safe closure, Ethan actively engaged with the process and made the decision for Firefly to move forward with transition. Project Families connected him with respected peers within his own country who had already gone through the transition and provided him with case studies of successful transition from the geographical region. Stories of individuals who remained involved in post-transition programming were highlighted, particularly in cases where they retained their salaries or were able to maintain comparable standards of living through the support of the principal donor.

Significantly, as Ethan had experienced a period of separation from his own family as a young child, he was able to empathize with the children living in institutions and realized that the institutional setting made it impossible for directors to provide the love and attention children needed to thrive. He said, “Being an orphanage director for 12 years, I know my relationship with the children. Even if we are open to them, they cannot be open to us. It is still the teacher-student relationship, not the parent-son relationship. In front of us they do not dare to tell us their feelings.” Despite holding a range of mixed motivations for involvement in institutional care and being naturally inclined to a rational approach, Ethan was able to empathize with the children in his care through his personal experience and demonstrated genuine concern for them.

Alongside the monthly working group meetings with the participating directors, Project Families’ donor engagement work with Together for Change included identifying other donors that were also financially supporting their partner institutions, and seeking to bring them onboard a transition process. For those who agreed to transition, a peer group was established to bring all of the involved donor organizations together to provide support to each other as well as to ensure consistent messaging to the institution directors regarding the agreed expectations of transition.

All of the participating directors and donors were signed into written agreements outlining concrete markers of progress and standardized responses to any child protection allegations emerging throughout the transition process. Together for Change frequently reiterated their commitment to fund the institutions fully participating in transition, and to phase out of funding those that chose to continue to provide the institutional care model. It was only after this preparation period that full buy-in was secured and the social work process could commence.

During the course of Project Families’ donor engagement work, Together for Change learned of another donor organization, Smiling Hearts Foundation, that had also been a long-time supporter of Firefly. Photos of Ethan with the children in his care were discovered on Smiling Heart’s website; however, the name of his institution was not listed as Firefly but instead identified as Smiling Hearts Children’s Home, named after the donor organization. Neither Smiling Hearts nor Together for Change was aware of the existence of the other donor as Ethan had not disclosed this information. Together for Change contacted Smiling Hearts, and with some effort managed to secure their support for the transition. From that point forward, both donors worked together to cross-check and verify past and future requests for financial support.

For children whose families were in a patron-client relationship with Ethan, concerns were raised around his possible interference with some of the family assessments, presumably to prevent children from returning home before he could fulfill his social obligations to provide long-term support for their education. Social workers responded by discreetly reporting their concerns to Project Families, and plans for his post-transition role were moved forward to justify his removal from social work and reintegration programming in a way that allowed him to save face. Where possible, community development initiatives aiming to prevent family separation were directed towards Ethan’s home community so that he could fulfill his social obligations as a patron and maintain his status in the community in alternative ways that did not rely on the institutionalization of children.

The partnership between Ethan and Together for Change was a highly relational and unstructured one, with absolute trust placed in Ethan and a profound lack of accountability for finances. Firefly was neither registered to operate as an institution, nor was it operated by an organization or any other entity. Ethan was treated as an employee of Together for Change for years before an employment contract was put into place.

Despite Ethan’s repeated requests for Together for Change to conduct a financial audit of the meticulous records he had kept of his own accord, they dismissed the need and continued to transfer large amounts of funds into his personal bank account. At times Ethan would have the equivalent of USD$200,000 of transferred funds in his bank account and he would often be asked to withdraw and store tens of thousands of dollars at his home until he could distribute the cash to other institutions supported by Together for Change.

Together for Change also relied on a child sponsorship model as their primary method of fundraising and private information about children was shared publicly and widely, without an awareness that this violated the rights of children to privacy. Visitors from overseas interacted with children at Firefly during annual visits, distributing gifts and requesting private details about the children’s histories.

As part of the onboarding and preparation work required in advance of commencing the social work process, Project Families worked in collaboration with both stakeholders to develop and implement a transition strategy. Key gaps were identified through the organizational assessment and plans were put in place to mitigate the numerous risks inherent in the relational partnership. This included the development and strengthening of organizational, governance, financial, and child protection policies and frameworks.

In later conversations, Ethan shared his reflections on the initial awareness-raising workshop delivered by the international training organization, as well as subsequent training sessions they delivered on social work processes. Two particular messaging tactics did not contribute whatsoever to his decision to transition away from institutional care: the child rights framework and the introduction of foster care. As these concepts were abstract and largely unfamiliar to most of the institution directors, he found them to be irrelevant to his situation until multiple in-depth conversations with Project Families guided him through breaking down such theoretical arguments into practical applications.

Notably, Ethan cited one specific message from awareness-raising workshops as particularly impactful on his decision to transition Firefly. Evidence of care reforms already taking place in other countries in the region led him to the realization that regardless of whether directors came on board with the idea of family-based care, institutional care would eventually be phased out in his country. Although Ethan became involved in institutional care through mixed motivations, his disposition towards a rational approach meant that a logical explanation of why it would no longer be feasible to remain in the business of institutional care, as well as hearing examples of others who were able to successfully retain their position post-transition, were effective in achieving buy-in for transition.

Together for Change now employs Ethan in a new role through which he delivers awareness-raising workshops on the importance of family care. He travels extensively to villages within his home province and speaks to parents and community leaders from his perspective as a former institution director. He is also involved in community development initiatives to improve local government schools so that parents can care for their children at home instead of sending them to institutions in the hopes of accessing better education for them. All but two of the children at Firefly have now been reintegrated with birth families or placed into kinship care. The remaining two children are working together with a Project Families social worker to prepare to leave care and transition into independent living.

SCORING

RATIONALE FOR SCORING AND TRANSITION STRATEGY

The combination of several potential risk factors led to a moderately complex but unexpectedly successful transition process. The mixed motivations and personal vested interests of the director could have posed a significant challenge to transition, particularly around retaining his status and livelihood as well as fulfilling social obligations to his clients.

However, as his decision to establish an institution was primarily a rational one instead of an emotional one, a rational approach to addressing his motivations and concerns around maintaining his status and livelihood post-transition proved effective in achieving buy-in for transition. While this message had to be delivered indirectly and sensitively so as to avoid accusing him of harboring personal vested interests, it was possible to openly connect him with others who had undergone transition to help him visualize how he could continue in a new role post-transition.

Although the director did not have relevant professional qualifications or experience, his tertiary education provided him with the capacity to quickly absorb new theories and processes around safe reintegration and community development. As such, he was involved in some of the case work for children in his care and, relying on his knowledge of the children’s histories and their time in care, he was able to make valuable contributions to the child assessments that social workers were undertaking. These contributions are typically missing from other transition projects where directors are either unable to grasp the importance of the assessment process or refuse to cooperate in providing information, resulting in gaps that can easily lead to inappropriate placement decisions and potential harm to children.

Overall the highest risk to the transition process was the lack of formality and structure to the partnership between the director and principal donor. As part of establishing organizational-level processes designed to work towards a contractual partnership, new structures were put into place around financial reporting and accountability systems. Direct dialogue was also facilitated between the director and principal donor about the need to change past practices and clarifying the conditions and expectations for the director’s future involvement in post-transition programming.

The director and principal donor’s inadvertent engagement in unethical fundraising was addressed by putting in place a robust child protection policy outlining ethical communications, as well as reforming the child sponsorship model to a family support model of fundraising that no longer distributed individual photos or disclosed private details regarding the children in the institution.

While the principal donor and director were quick to genuinely buy into the concept of family-based care, the process of risk mitigation was critical to ensuring a safe transition process. Culturally sensitive approaches and creative solutions were required to address the director’s mixed motivations and to resolve some of the issues emerging from the director operating within his role of patron to the families of children in his care.

Despite the presence of several orange- and a handful of red-light indicators, transition was feasible through the careful navigation of all of these aspects. The outcomes of the transition have been largely positive and the director has emerged as a strong candidate for a national care reform advocate.

CASE STUDY: LIGHTHOUSE CHILDREN’S VILLAGE

(Spanish version)

In 2004 a Norwegian woman named Kim traveled overseas with a friend and was introduced to an expatriate couple involved in charity work with communities living near a rubbish dump. When the expatriate couple met a young national woman named Maya who had grown up in an institution and wanted to establish her own, they co-founded Lighthouse Children’s Village together. Maya took on the role of co-director and the primary caregiving role, while the expatriate couple filled the dual role of principal donor/co-director by taking on both the primary fundraising responsibility in addition to management of the day-to-day operations of Lighthouse. Through her deepening relationship with the expatriate couple, Kim became increasingly involved with Lighthouse and brought teams over on an annual basis to volunteer and interact with the children living there.

In 2004 a Norwegian woman named Kim traveled overseas with a friend and was introduced to an expatriate couple involved in charity work with communities living near a rubbish dump. When the expatriate couple met a young national woman named Maya who had grown up in an institution and wanted to establish her own, they co-founded Lighthouse Children’s Village together. Maya took on the role of co-director and the primary caregiving role, while the expatriate couple filled the dual role of principal donor/co-director by taking on both the primary fundraising responsibility in addition to management of the day-to-day operations of Lighthouse. Through her deepening relationship with the expatriate couple, Kim became increasingly involved with Lighthouse and brought teams over on an annual basis to volunteer and interact with the children living there.

After a period of supporting the expatriate couple through worsening medical, mental health, and personal issues that ultimately prevented them from continuing in their roles with Lighthouse, Kim took over the role of principal donor. The expatriate couple were removed from their positions and a Norwegian entity was established to raise and disburse funds to Lighthouse. As the new principal donor, Kim took steps to put measures in place for organizational and financial accountability of Lighthouse, and she also undertook a comprehensive update of the child sponsorship program.

Kim soon realized that the number of children that she had been raising funds to support was different from the number of children that actually lived in the institution. She was unable to reconcile some of the photos of children with previous ones, as unbeknownst to her, new children were replacing those who had previously lived at Lighthouse. Extensive questioning of various people led her to discover that many of the children did indeed have parents and that some of them went in and out of care. Children who were supposedly orphans had families to return to during public and school holidays and were visited by parents who passed them food through the gates because they were not allowed inside Lighthouse.

During this time, the national co-founder and director, Maya, had often come into conflict with the expatriate couple but had primarily remained in the background and had not had much contact with Kim. As the expatriate couple’s return to Norway became imminent, Maya invested heavily in her relationship with Kim, presumably to retain access to funding. Maya’s husband, Liam, also a national, was hired as the new acting manager of Lighthouse and he effectively became the director, taking charge of the daily operations and becoming the primary liaison to Kim. At this point, Kim was seeking another organization to permanently take over the management of Lighthouse, partially due to the stress incurred around the management changes and partially due to an increasing difficulty of raising funds for the institution.

When Kim approached Transform Care Foundation, an organization advocating for family-based care, she requested that they take over management of Lighthouse. Encouraging her to work towards transition instead, Transform Care supported Kim to begin the process of gathering information to develop a transition strategy. Based on Transform Care’s familiarity with the cost of living in the country where Lighthouse was operating, one of the first areas identified as a red flag was the inflated budgets Maya and Liam were sending through to Kim on a monthly basis.

Kim had inherited from the expatriate couple the financial responsibility of covering rent for a lavish building that Maya and Liam used to house themselves and several of their extended family members, monthly salaries for both directors that were well above what they should have been in comparison to similar positions in other organizations, and private school tuition for their three biological children. While this was a clear warning sign to Transform Care, raising concerns about the possibility of financial misappropriation at this stage would have been premature, given the close relationship and loyalty that had formed between Kim and Maya and Liam. Every call they had regarding Lighthouse operations and funding ended in declarations of their love and respect for each other, and Kim was convinced that despite their inefficiency in financial management, they genuinely cared about the children.

After a period of in-depth discussions with Transform Care exploring the possibility of transition, Kim and board members of the Norwegian funding entity made the decision to move forward. While they believed in the benefits of family care, they had no reason to doubt that Maya and Liam were providing good care for the children at Lighthouse. As a result, the overriding factor in their decision to pursue transition was more about decreasing the responsibility of management and financial burden on themselves and their supporters than it was about an urgency to reintegrate children out of a harmful situation.

When Kim presented the idea of transition to Maya and Liam, they agreed to participate relatively quickly and signed a partnership agreement together with Transform Care and the Norwegian entity, outlining terms for phasing out of institutional care and exploring post-transition programming. It would later become apparent that they had agreed to transition with no intention to do so, and their efforts to undermine the process resulted in mixed messaging to children and families as well as compromising the reintegration process itself.

Following a period of assessing and strengthening organizational systems and policies for both the Norwegian entity and Lighthouse, an external social worker was hired to outwork the reintegration process with the children at Lighthouse. Through her work there, she came to suspect widespread abuse and was subject to harassment and threats by the directors in response to her reporting of allegations in accordance with Lighthouse’s new child protection policy. Her efforts to conduct child assessments were hampered by Maya and Liam as they instructed children not to speak with her and threatened them if they did. They called families ahead of her visits and instructed them to inform her that they could not care for their children and did not want them to leave Lighthouse. They also intentionally misinformed families and children that Transform Care would pay the social worker a commission for every child she reintegrated.

Over the course of six months, Transform Care carefully presented to Kim evidence of Maya and Liam’s interference with the reintegration process, intentionally revealing small pieces of information at a time. Because the relationship between Kim and Maya and Liam had been cultivated for nearly ten years and Kim’s loyalty to them was based on a deep sense of trust, premature accusations of unethical behavior could have resulted in Kim’s inability to objectively see Maya and Liam’s actions. Kim could have easily come to their defense if she felt that they were being unfairly accused by an organization that barely knew them, and she might have rescinded on her decision to transition. Despite suspicions that not everything was above board in the operations of Lighthouse, Kim excused their behavior with the justification that they were good people who cared about the children.

When the social worker resigned after four months of employment and Maya and Liam’s sabotage became increasingly apparent and inexcusable, Transform Care advised Kim to pay an in-person visit to Lighthouse to collect documents that might reveal evidence of the suspected financial misappropriation. While the allegations of abuse and the directors’ interference with efforts to reintegrate the children were the most concerning of issues, Transform Care instead chose to pursue evidence of their financial misappropriation as grounds for termination of their employment. Rather than involve children in a potentially unsafe situation whereby Maya and Liam could pressure or threaten them to retract their disclosures, the goal was to remove the directors from Lighthouse so that the children would no longer be in their care.

In response to Kim’s visit and request for financial records, Liam realized that he was cornered, and acting out of desperation, he physically assaulted Kim and blocked her from leaving the office until Maya finally intervened, pleading with her husband to let Kim go. As Maya and Liam had been forced to show their true colors to Kim, plans were made to terminate their employment following staff disciplinary procedures. Kim’s allegiance shifted immediately and fully to the children and all efforts were focused on ensuring their safety.

It was then that Lighthouse’s governance documentation revealed that the overseas board members were not legally registered as a governance board with the appropriate government department, despite falsified documentation and assurances from Liam that they had been. Although staff contracts had been put in place as part of the preparation work prior to commencing reintegration, a review of the paperwork revealed that they had not been signed by the directors or other employees. Without any organizational structure or legal authority to remove them from their positions, Kim agreed not to press charges for the assault in exchange for Maya and Liam’s voluntary resignation and a generous severance package.

Once a transitional board and management team were put into place, counselors and psychologists were sent in to work with the children and staff who were all reeling from the unexpected departure of the former directors. Many of the children remained in close contact with Maya and Liam and carried out their instructions to vandalize the property, physically threaten the new social workers with shards of glass, and report to Kim false claims of abuse by the new manager. Older children who had spent up to ten years at Lighthouse felt lost at having their caretakers sent away without explanation, as Kim could not explain to them that Maya and Liam had been exploiting them for their personal profit. Although a comprehensive review of financial records would later reveal that the directors had taken the equivalent of USD$50,000 for themselves out of donations and funding for Lighthouse, Kim had signed a non-disclosure agreement that prohibited her from speaking of the reasons for the directors’ resignation.

As the new management team tracked down care leavers that had left Lighthouse and listened to their accounts of what they had witnessed during their time in care, details emerged of cases involving sexual abuse perpetrated by a female caregiver staff member who also happened to be Maya’s sister. Older children were instructed by Liam to use physical violence against younger children to cause chaos within Lighthouse. Young people had been sent away from Lighthouse after learning to speak English well enough to be able to communicate to Kim evidence of the financial misappropriation and abuse they had discovered.

In the latter cases, Maya and Liam falsely accused the young people of stealing money or engaging in prostitution to publicly discredit them and cast doubt on any allegations they might make. This involved shaming the young people in front of their families and communities in order to take away their existing support networks, ultimately leading to the incarceration of one young person and, for another, involvement in sex work leading to irreparable damage to her relationship with her mother.

In one of the most severe cases of neglect and abuse, Maya and Liam went to great lengths to cover up their failure to provide medical treatment for a young child who was left unsupervised and sustained a brain injury in an accident. They found his resulting cognitive and physical impairments too difficult to cope with, and as the child’s condition deteriorated, the directors sent him away to a rural province to be cared for by a childless couple until his death, eight months after the accident.

As social workers began to track down most of the families of the children in care, stories surfaced of how parents of children who had been recruited into care were unaware of their children’s whereabouts and had searched for them for years. Written contracts preventing parents from visiting or contacting their children were discovered within the children’s files, threatening the confiscation of the parents’ national identification cards if they breached the contract terms. Most of the information given by Maya and Liam regarding the situations of the families turned out to be false, and there were credible suspicions that some children had been trafficked into care from across the country by Liam’s colleague.

When the individual suspected of trafficking attempted to remove those children from Lighthouse during the transition process, displaying falsified birth certificates and claiming that they were his adopted children, the situation was reported to local police and authorities, as well as the national government child welfare department responsible for overseeing residential care services for children. After months of several meetings with the senior government official representing the child welfare department resulted in no action, it came to light that he had a long-standing friendship with Liam and he ultimately chose not to exercise his duty of care to the children.

As it became clear that Maya and Liam were continuing to work behind the scenes to sabotage the new management team and the reintegration process, the decision was made to move the children into two small group homes in a different area of the city, firstly to remove them from the physical environment where many had endured years of abuse and the resulting culture of violence, and secondly to increase the geographical distance from Maya and Liam. Children and families were consulted, sibling groups kept together, younger children separated from older ones who were physically abusive, experienced caregivers hired, typical houses indistinct from others in the community rented out, and children enrolled into new schools.

As the counselors and social workers continued their work, the children began to thrive almost immediately. Levels of violence drastically reduced, high-risk behaviors decreased, school progress soared, and within 18 months, all of the children had been reintegrated into family or community-based care settings. A program for care leavers was established to support them to safely transition into life outside of Lighthouse, and some of the young people slated for independent living even decided to return to their families. While monitoring of most of the cases is ongoing and social workers are still faced with numerous challenges and risk of placement breakdown, none of the children have been reinstitutionalized and most are faring reasonably well, considering the years of abuse and trauma they all endured.

During the four years that followed Kim’s decision to transition, she endured unfathomable levels of stress and internal conflict as she struggled to cope with the overwhelming sense of betrayal from the actions of Maya and Liam. As more details were uncovered regarding the abusive and criminal behaviors of multiple individuals associated with Lighthouse, Kim witnessed firsthand the vicious backlash for having exposed all of it. Kim simultaneously faced multiple emergencies and health issues within her own family, and refinanced her house and sold personal assets to be able to continue funding the transition process. She remains engaged in legal battles with Maya and Liam to this day.

In a rare display of unwavering commitment to children, Kim stayed engaged with the transition process even when she was emotionally and financially drained and felt she could not continue. Although similar situations have been known to fail spectacularly with untold damage done to children, the combination of circumstances and interventions resulted in an unlikely story of a group of people who chose not to walk away and the children whose lives were changed because of it.

SCORING

RATIONALE FOR SCORING AND TRANSITION STRATEGY

While the principal donor demonstrated genuine concern for the children’s well-being alongside a deep sense of loyalty to the directors for their work in caring for children, the directors’ motivations for involvement in institutional care were overwhelmingly dominated by the pursuit of financial profit. The initial motivations of the national founding director for establishing an institution were never made clear but she reaped the benefits of the profit-seeking actions of her husband.

As he had effectively replaced her in her role as director by the time the transition commenced, she initially appeared to have been merely complicit in the deception without instigating it. However, as further allegations surfaced throughout the course of transition, it became clear that she had gone to extreme lengths to put children and young people at harm in an effort to protect herself and the institution, and to ensure that funding would continue to flow from the principal donor.

The presence of these motivations that superseded the best interests of children, combined with a highly relational and trust-based partnership, set within a country with weak regulatory frameworks, created a volatile situation that resulted in an institutional culture of abuse of power over staff as well as children and their families. Although key gaps in organizational processes were identified, it was in the interest of the directors to prevent efforts to address them.

Having agreed to transition without ever having had any intention to change their model of care, the directors went through the motions of appearing to cooperate while undermining and sabotaging any possibility of real change. They contacted other donors in an effort to secure funding from other sources, including attempts to establish a new institution and coerce children into following them. Until the resignation of the directors was negotiated and the children physically moved away from their proximity, it was nearly impossible to effect any positive influence and commence the social work process.

When the principal donor initially agreed to transitioning away from supporting institutional care, the overriding reason for the decision was not necessarily a realization that children should be in families. Believing that the children were well cared for, they could see phasing out of institutional care as a solution to the challenges they faced in funding a long-term and ongoing commitment, and that it could also resolve their concerns that the directors were not managing the institution in a cost-effective way.

However, when suspicions of more serious unethical and criminal behavior arose and were later confirmed, the principal donor’s motivation for pushing forward with the transition transformed into focusing completely on the safety and well-being of the children. Amidst an enormous sense of betrayal from uncovering years of deception, financial profit, abuse, and exploitation at the hands of people she had fully trusted and vouched for, it was the responsibility she felt towards protecting those children that kept her involved in a transition process that most others would have abandoned.

It bears noting that many of the interventions employed throughout this transition were only feasible in this situation because of the technical support-providing practitioners’ direct experience of living and working for many years within the country where the institution was operating. It is unlikely that these interventions could have been carried out by international practitioners unfamiliar with the context and unable to rely on extensive networks and existing relationships with individuals, organizations, and local authorities for assistance. Thus it is recommended that any use of the interventions described here should be carefully considered within the context of other transitions.

Additional Case Studies:

- A Case Study of Malaika Babies Home Uganda

- A Case Study of Engaging Everyone in the Transformation: Child Rescue Centre and Helping Children Worldwide

Transitioning Care Assessment Tool Overview

Overview for Transitioning Organizations

Introduction

Transitioning residential care centers is an important part of care reforms. As organizations running residential care services go through the process of transition, they redirect efforts and investment into critical family- and community-based supports that make it possible for children to grow up in a family and as part of a wider community.

Transitioning a residential care center is a broad process that involves changes at every level of the organization. It is complex and there are many different stages and steps in a transition process, as outlined in the diagram below:

A tailored approach to transition

While most transitions progress through these overarching stages, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. This is because no two residential care centers are the same. Each has a unique starting point that is a combination of the country and cultural context in which it exists, and the dynamics that are unique to the organizations, partners, and individuals involved. As such, each one requires a tailored strategy to support transition in a way that is safe and effective.

The Transitioning Care Assessment Tool was developed to assist practitioners providing technical support to organizations undergoing transition develop such a tailored strategy. It focuses on the perspectives and concerns of the key stakeholders, and particularly the partnership between those running the residential care center and their key supporters. It is a sense-making tool that guides practitioners through the process of analyzing the dynamics involved. The dynamics are organized around seven key themes and the tool suggests relevant tips and actions that practitioners can factor into their strategic plan. It is designed to supplement, rather than replace, other assessment tools such as child and family assessments and organizational assessments.

What is Required?

Before using the Transitioning Care Assessment Tool, practitioners providing technical support should first possess a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory frameworks, policies, and legislation of the country within which the institution is operating. This includes a working knowledge of:

- National child protection frameworks

- Social welfare support services

- Alternative care policies

Next, a number of organizational assessments should be conducted and relevant information gathered from the key stakeholders, i.e., the director and the principal donor. This information may relate to the following areas:

- Governance

- Organizational structure and status

- Partnership·Founding history

- Perspectives of the stakeholders

Once this information has been gathered, it will then be possible to work through the Transitioning Care Assessment Tool to analyze the practitioner’s individual situation and develop an appropriate transition strategy.

What else is included?

The Transitioning Care Assessment Tool contains links to other useful resources that practitioners may want to use or adapt to outwork the transition. It also includes some brief overviews of sociological theories and perspectives, such as relevant cultural paradigms, that relate to transition.