Welcome and Background to the Tool

This tool evolved from the learning and experience of the authors throughout their work to transition privately-run and funded residential care institutions in various countries and regions. Over time, the authors observed trends and key indicators that enabled them to anticipate how a transition might unfold.

These trends and key indicators often stemmed from dynamics linked to the motivations and characteristics of the director and principal donor of a residential care facility (RCF) , and the relationship and history between them. These dynamics created the ‘starting point’, or in other words, the enabling environment. By analyzing the enabling environment, the authors found that they could anticipate the potential path of a transition and use these insights to develop the safest and most effective strategy possible. The documentation of these learnings and trends spanning many years led to the development of this tool.

Background

Care Reforms: The Big Picture

The detriments of residential care on children’s development and wellbeing are well-documented and well-established. The overwhelming evidence has led to a global call to end the institutionalization of children and has catalyzed child protection and care systems reforms in many regions and countries.

Care reforms are complex and entail multi-faceted changes at the systems level. They involve changes made to legislation, regulation, policy, services, resource allocation, and workforce training, as well as the development of new mechanisms for implementation and monitoring. They are government-led and often supported by inter-governmental and non-government agencies.

In countries where there is an over-reliance on residential care, a key goal of reform efforts is to reorient the care systems towards family-based solutions, recognizing:

a. the family as the optimal environment for children’s development and wellbeing;

b. the right of the child to family-life;

c. the obligations of States to provide support to parents to fulfil their caregiving responsibilities towards children; and

d. the priority given to family-based alternative care in international norms.

This type of reform is often referred to as ‘deinstitutionalization’ and includes efforts to reduce the number of children in RCFs through reintegration and scaling back the number of RCFs in operation, ideally through transition rather than closure. Transition is therefore a component of care reforms and should, to the extent possible, be linked to broader systems-level reforms, take place with involvement from the mandated authorities, and use established national procedures where they exist.

Transitional as the Ideal

Transition, as the name suggests, involves changing an organization's model of care or services from residential to non-residential ones. Transition, rather than closure, is ideal as it serves two purposes. Firstly, it contributes to the decrease in the number of RCFs. Secondly, it allows new services to be developed that support children to remain in families. This happens when human, financial, and material resources used to sustain the RCF are redirected and repurposed. Therefore, transition aims to shift resources away from residential models but retain investment in child and family welfare systems.

Some organizations transition into programs that are set up to support the children reintegrating out of the transitioning residential care services. In other cases, new programs are developed to address a gap in the overall system that will continue to result in children being placed in residential care unless addressed. New programs do not have to be limited to family-based alternative care services, such as foster care and kinship care. They can include community programs related to education, disability, daycare, child-centered community development, or positive parenting. These programs all contribute to efforts to strengthen systems such as social protection, education, child welfare, or child protection, all of which will impact children’s care.

What Does Transition Involve?

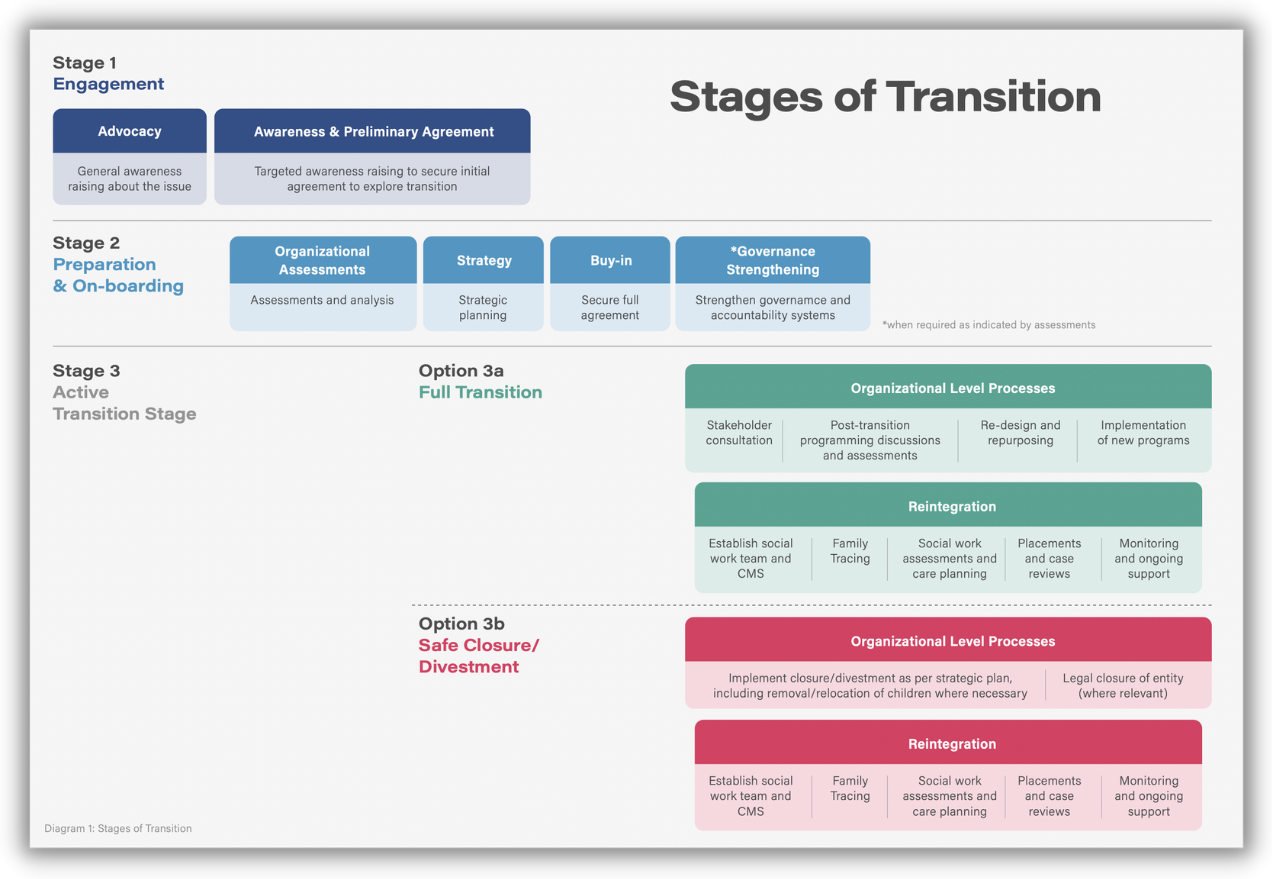

Many people view transition of a residential care service as the same or similar to the reintegration process of children. While reintegration is one of the most important outcomes, transition is a much broader process. It involves change at every tier of the organization running the RCF. This includes structural, policy, procedural, programmatic, and resourcing levels. As outlined in the diagram below, there are many stages and steps that need to take place before reintegration begins. Overlooking these critical stages can negatively impact the entire transition process and outcomes for the children. Transition strategies should be tailored to each organization, taking into account their unique starting point. If they begin by lacking sufficient structure or reporting procedures, strategies may need to address this to manage the change process, mitigate risk, or respond to any incidents that may emerge during transition.

Degrees of Success

There are a number of key outcomes associated with transitioning a residential care service, all of which contribute towards systems level care reform.

|

Organizational Level Outcomes |

Systems Level Outcomes |

| Safe reintegration of children in the RCF back into families and communities | Reduction in the overall number of children in residential care |

| Divestment of human, financial, and material resources from an individual RCF | Reduction in the overall number of RCFs in operation |

| Reinvestment of human, financial, and material resources in family strengthening services or family-based alternative care | Development of non-residential services as alternatives |

In an ideal transition scenario, all three of the organizational level outcomes would be fully achieved, resulting in a full redirection of former resources towards non-residential services. However, this is not always possible. There are some situations in which full transition is not the appropriate goal and could even place children at risk of harm. This is particularly the case where there is insufficient commitment to delivering high quality services, serious capacity or child protection related concerns, or mixed motives revealed in the assessment. These types of concerns may call into question the suitability of the directors, staff, or other stakeholders working directly with vulnerable children. In such instances, a more appropriate goal might be safe closure. This can be voluntary or enforced by the relevant authorities in more serious cases or as part of national efforts to scale back residential care in the country. Depending on the context and nature of concerns, it may be entirely appropriate for directors and staff to transition into non-child welfare related projects.

While safe closure of an residential care, in the absence of full transition, may not be the ideal or best-case scenario, it is a valid outcome and should not be perceived as failure. This is because safe closures still make important contributions to the systems level reform including the following outcomes:

- a reduction in the overall number of children in residential care through safe reintegration; and

- a reduction in the overall number of RCFs in operation through safe closure.

In some cases, a safe closure may also achieve the desired goal of reinvesting financial resources in non-residential care services in a slightly different way. Donors who supported the RCF undergoing closure can be encouraged and supported to reinvest their finances in other organizations running family strengthening services or family-based alternative care. This allows for the scaling up of existing alternatives run by organizations with demonstrated capacity and expertise.

Therefore, it is important to view success in transition work as inclusive of a continuum of outcomes and impacts, which all must be achieved in a manner that is safe and in the best interests of children. A realistic framing of success from the outset will enable practitioners to develop appropriate monitoring and evaluation frameworks. It is also critical to sustaining motivation and dedication in the face of complex and challenging work.

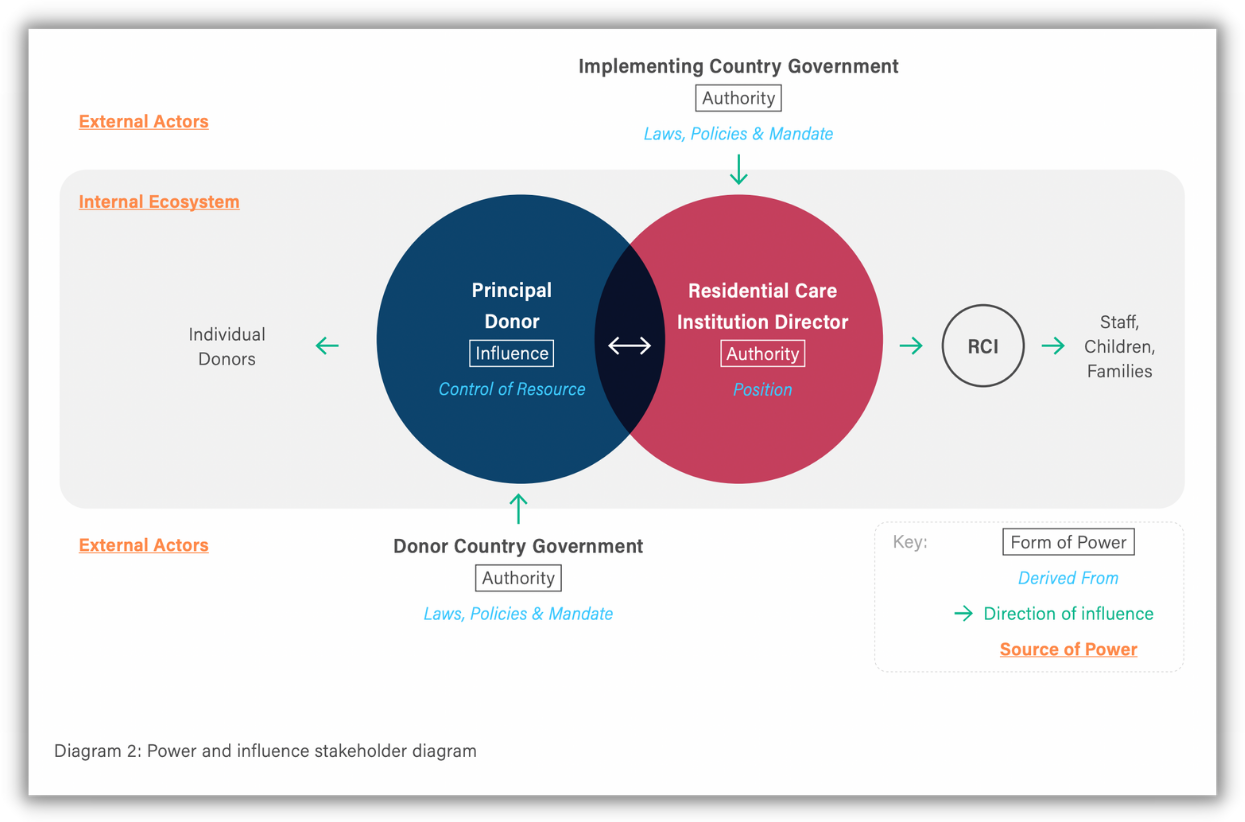

Power and its Impact on the Decision to Transition

In order to effectively outwork the transition of a residential care service, it is necessary to understand the power dynamics between the key stakeholders and work strategically with this knowledge. Power takes different forms and comes from various sources. When it comes to decision-making, including the decision to transition, power is typically held by three key stakeholders:

- Government

- Director

- Principal Donor

Governments in both donor and implementing countries exert different levels of power and influence on a transition. This is based on the strength and effectiveness of existing laws, policies, regulation, inspectorates, and child protection response mechanisms.

This is not only true of governments in countries where the institutions are operating. It is also true of governments in donor countries whose laws and regulations impact charities’ operations and fundraising efforts. In some cases, this includes regulations around funding or operating overseas RCFs.

Power & Influence Over Residential Care

Having well-established and resourced government systems in countries where the RCFs are run can certainly make it much easier to implement a transition and provides critical government support should issues arise. It can also result in governmentmandated transitions or closures, which lends full government authority to the process. In many contexts where reforms are underway, relevant laws and policies often exist.

However, government resources are limited, and systems are in the early stages of development. This reduces the likelihood of transitions being enforced by government mandates or power. In these situations, it becomes even more critical to tap into the influence and power structures within the internal ecosystem of a given RCF, both regarding buy-in and the development of a transition strategy.

Working with Decision Makers in the Internal Ecosystem

The internal ecosystem of an RCF is comprised of a range of stakeholders including:

- the director of the facility;

- the staff and caregivers of the institution;

- children and families;

- partner charities and organizations supporting the RCF;

- individual donors supporting the RCF;

- and the original founder of the RCF.

- In some cases, the founder may also be the director or principal donor, or sometimes both.

- In other cases, the founder may have stepped out of an active role with the institution and has limited or no involvement.

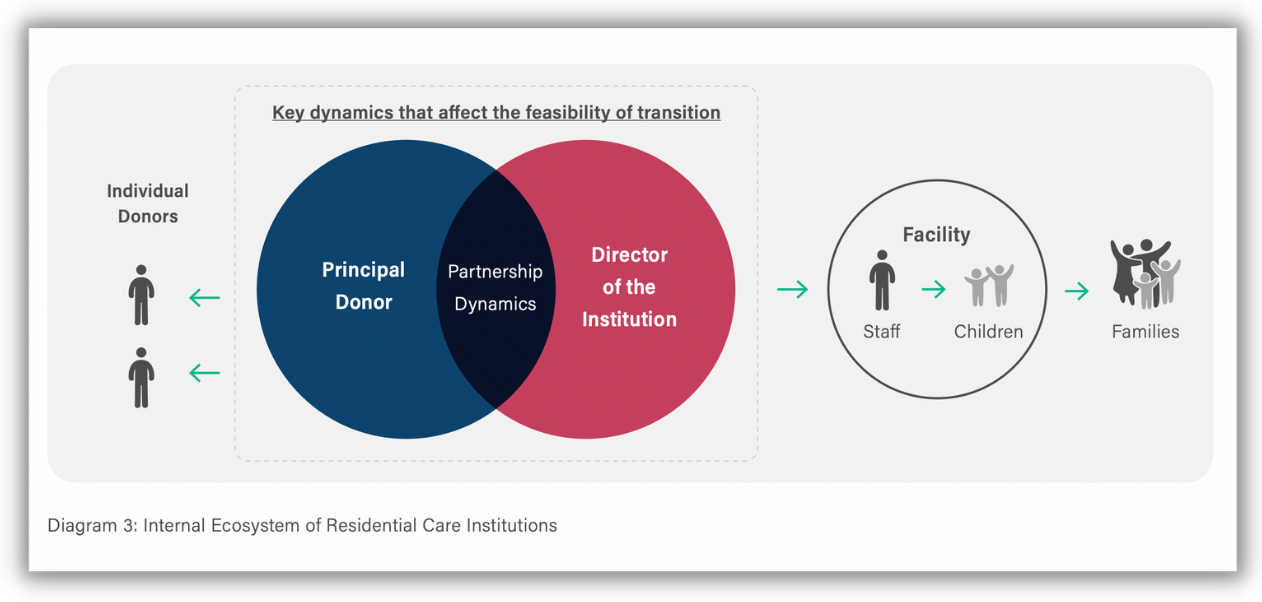

Internal Ecosystem of an Institution

In this ecosystem, all of these stakeholders have an important role and need to be onboarded to ensure an effective transition. However, the two key stakeholders who exert the most significant influence on organizational decision- making and therefore the process of transition are:

- The director, who has operational control over the RCF, including staff and caregivers; and

- The principal donor, the person who represents the main or largest donor, or primary fundraiser. The principal donor, the person who represents the main or largest donor, or primary fundraiser.

The principal donor:

- can be an individual or entity;

- typically represents a charity, organization, church, family trust, or business that is funding the institution;

- often collects donations from individual donors and is the channel through which individual donations flow to the RCF;

- typically manages the communication with individual donors; and

- in rarer cases, financially supports the RCF independently.

In some cases, the founder of the RCF may have transitioned from the role of director into the role of principal donor.

Note: It is not uncommon for RCFs to be run by married couples. While there may be one person who seems more prominent and engaged in the discussions, the perspectives of both spouses are likely to have an influence over the decision to transition. It is therefore important to consider this dynamic and the possibility of divergent perspectives or motives between spouses while working through this assessment tool.

Identifying the director and principal donor as the two key stakeholders does not diminish the important role that staff play, nor does it ensure that they have bought into the transition process. Rather, it recognizes that the director has operational control over the RCF. This includes operational control over the staff. The director is therefore a gatekeeper to those relationships and is the primary person who will either manage or undermine staff cooperation, implementation, and compliance with operational decisions.

In the same sense, recognizing the principal donor as a key stakeholder does not undermine the presence of, or importance of working with, other donors. It realizes the likelihood of the largest donor having the greatest influence on the decision to transition and its effective implementation.

It is for this reason that the director and principal donor are identified and referred to throughout this tool as the ‘primary stakeholders’. Throughout the tool, there are also recommendations that address working with staff and other donors.

The director and principal donor act as the two entry points into discussions about the possibility of transition. Practitioners may first engage with the director of an RCF for the purpose of securing buy-in for transition. Alternatively, they may connect with the principal donor in order to exert influence through the funding stream. Both entry points are valid, but both might not be equally effective, due to different partnership dynamics.

Definitions of key terms used throughout the tool

| Director | Refers to the director of the residential care facility |

| Principal Donor | Refers to the person who represents the main donor (primary or largest) or is the primary fundraiser who acts as the conduit of funds raised from smaller individual donors |

| Stakeholder | Within the assessment section, refers to the Director and Principal Donor |

| Practitioner | Refers to the person/s providing technical support to the organisation running an RCF for the purpose of transition |

In privately-funded RCF, principal donors are quite often better positioned to bring about change than directors, as they control the funds. However, as the power of most principal donors is influential rather than authoritative in nature, donors are rarely able to independently make the decision to transition. As such, a successful transition is dependent upon engaging both stakeholders in the discussion and decision-making.

This includes:

- Identifying the power dynamics between the director and principal donor and adapting the engagement strategy accordingly;

- Analyzing the partnership dynamics between the director and principal donor; and

- Identifying strengths and risks resulting from both sets of dynamics and factoring risk management strategies into the transition plan. The primary aim of this assessment tool is to guide practitioners through this process.

Overview of the Tool

Purpose of the Tool

This tool aims to assist practitioners to achieve the following objectives when providing technical support to transitioning residential care services:

- Determine the feasibility of implementing a successful transition by taking into account the number of positive indicators and/or severity of risk indicators.

- Extract and analyze critical information that informs the approach and allows the practitioner to develop a strategic plan and budget for transition.

The tool recognizes that because the starting point of each organization providing residential care services is different, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Tailored strategies need to be developed for each individual transition process, taking into account their unique dynamics. The tool has therefore been designed as an assessment framework that assists practitioners to identify and analyze these key starting point dynamics and determine the implications for strategy. In other words, it is a sense-making tool rather than a ready-made strategy. The tool can also be used on an evolving basis to help practitioners make sense of new information or indicators that arise throughout the transition process.

Whom the Tool is For

This tool has been written for practitioners who are guiding or providing technical support to third-party organizations operating residential care services, to undergo transition. Practitioners may be technical staff, child protection staff or social workers of local or international NGOs, or consultants. They may be providing transition support as an individual practitioner or as part of a multidisciplinary team. Practitioners may be providing technical support to transitioning residential care service under a number of arrangements including:

- as part of a program or service offered by their agency;

- as part of a partnership formed with the residential care service provider or with their donor entity for the specific purpose of providing technical support;

- as part of a contract or consultancy; or

- as part of a national deinstitutionalization plan which utilizes the technical expertise of a civil society partner to support transitioning institutions.

The tool is primarily designed for use in transitions involving residential care services that are:

- Privately run;

- Largely overseas funded; and

- Located in countries with emerging or weak regulatory frameworks.

The tool can be used regardless of whether the transition or closure is voluntary or mandated by government.

What the Tool is Not Designed For

It is important to recognize some of the limitations of the tool and situations that it was not designed for or where its use is not recommended. These include:

- Closure of government-run RCFs. Practitioners supporting the transition of government-run institutions may find some of this tool relevant and useful, particularly regarding stakeholder engagement in the implementation phase. However, it is important to note that the tool was not primarily designed with the transition or closure of government-run RCFs in mind. The process of transitioning or closing government-run RCFs can be quite different. It can be less complex in terms of the buy-in process and stakeholder management, because it takes place in response to a government directive. Practitioners are also less likely to be involved in the whole process of closure or transition.

- Self-assessments for organizations directly operating residential care services. The tool was not designed to be used as a self-assessment tool to support organizations that directly operate residential care services to independently transition. While it may provide some relevant learning and suggestions, it is not a transition training manual designed to walk an organization through each step of a transition process.

- Usage in interview settings with directors or principal donors of residential care services. The tool is designed to help practitioners make sense of the information they have collected, formally and informally. It is not a set of questions to directly ask the key stakeholders, or a survey or form to complete with, or in the presence of, stakeholders. Instead, practitioners can provide key stakeholders or partners with an overview of the tool on page 161 in the Annex, if they wish to provide a concise summary of the tools that they will use to develop the transition strategy.

- Usage by inexperienced or untrained practitioners. The tool assumes and requires a fair degree of technical knowledge of transition and therefore should be used by practitioners with sufficient training and experience. This reflects the complex nature of transition work that should not be underestimated or minimized.

- Usage as a reintegration manual. While reintegration is undoubtedly one of the most important outcomes of a transition process, the tool refers to the broader process of transition entailing multiple stages (refer to Diagram 1: Stages of Transition). It is not meant to provide guidance on how to outwork a reintegration process. Resources that are designed for this purpose can be found in ‘Useful Resources and Tools’ in the Annex.

When the Tool Should be Used

Practitioners will need to have a fair degree of existing knowledge about the director and principal donor to be able to use this tool. Therefore, the assessment component of the tool should ideally be used during Phase 2 of the overall transition process (refer to Diagram 1: Stages of Transition), after awareness-raising and organizational assessments have already been conducted. It is at this point that practitioners are likely to have gathered sufficient and relevant information to be able to complete the assessment, both from direct observations of, and interactions with, stakeholders as well as third-party sources of information. However, it is recommended that practitioners read through the tool prior to commencing Phase 1 of a transition as the content is likely to inform the approach to awareness-raising, organizational assessments, and information gathering.

If gaps in knowledge are identified during the process of working through the indicators, it is advisable to seek further information or clarity as far as is possible. This will ensure that practitioners gain the maximum benefit from the tool. Where certain information is not yet known, the questions can be used to guide practitioners to gather further information prior to finalizing the assessment.

Structure of Assessment

The assessment form contains a set of checklists containing a wide range of indicators and implications pertaining to the director and the principal donor as the two key stakeholders, as well as their partnership. This section is organized around seven key themes and broken into several sections

1. About this Theme

Each theme starts with an About This Theme section which provides a brief overview of the theory the theme draws upon. The theories have been summarized for practitioners who find the theoretical context useful. Others may find it more useful to skip straight to the more concrete indicators. On each ‘ About This Theme’ page you will find a training video that further explains the theme, how to assess for that theme, and includes a video case study from a partner organization demonstrating how that theme was expressed in their transition example.

2. Indicators

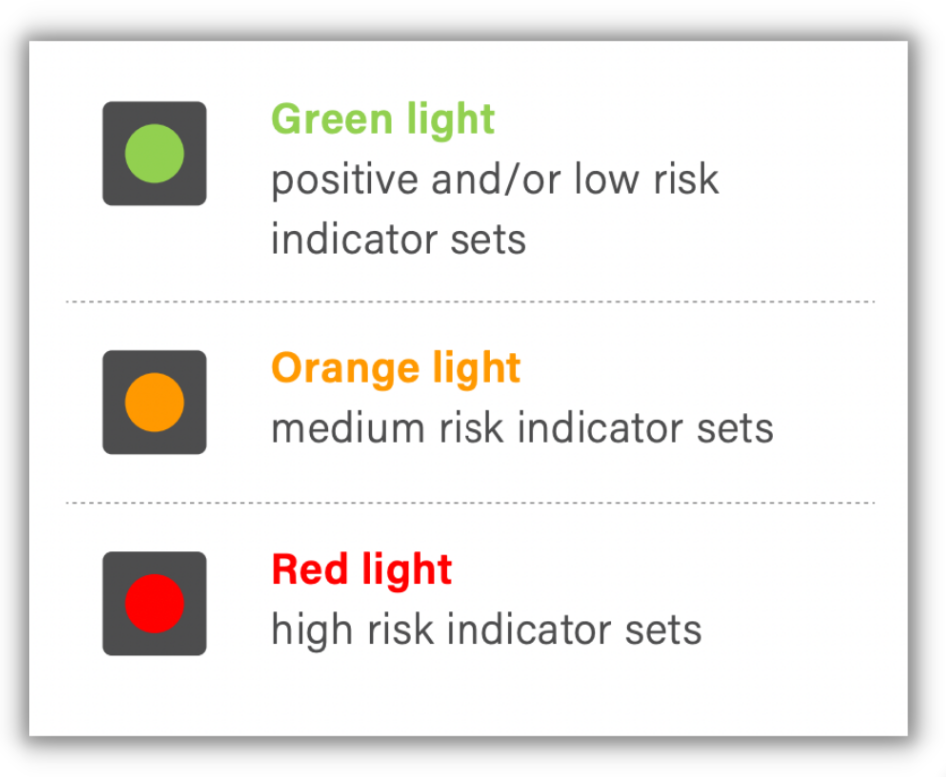

Next you will be taken to the indicators section. For each theme, practitioners can select the indicators relevant to, and representative of, the director and the principal donor, and the partnership between them. These are categorized using a traffic light risk rating system:

3. Score and Implications

After submitting your selection of indicators, a score will be automatically generated telling you which color category you have scored for that theme. A corresponding set of implications are then provided. The implications include the following sections:

- explanation;

- suggested actions;

- funding implications; and

- where relevant, notes and warnings designed to alert practitioners to risks and assumptions that could prove problematic.

The implications are based on trends observed across numerous transitions and are designed to help practitioners identify more subtle underlying issues. More concrete residential care assessment frameworks may not capture these underlying issues, but they are critical to consider as they can significantly impact on transition and, by extension, children.

The list of implications should not be taken as definitive or exhaustive, and this tool does not remove the need for practitioners to conduct in-depth assessments of the institution and children in care as a part of the transition process. An example of a residential care assessment form can be found here.

4. Overall Score

Once you have submitted your assessment for each theme, an overall score is generated using the same color traffic light system. This gives an overall risk rating and a sense of the following important dynamics:

- the presence of positive indicators that enhance transition;

- the level of complexity ranging from low to high;

- the related risks including risk of interference or sabotage;

- the type and level of technical support required;

- the implications for human and financial resources;

- the stage of transition that should be commenced within the overarching transition timeline; and

- whether a realistic end goal is transition to alternative services or safe closure.

Indicators and Implications

This section contains the indicator lists and corresponding implications. It is the assessment component of the tool and is designed to help the user collate and analyze information about the stakeholders and explore possible implications for the transition. The indicators and implications are organized around the seven key themes and broken down under each theme into categories using the traffic light system. The seven key themes are:

Resources

- Transitioning Models of Care Assessment Tool (PDF Version)

- Financial Impact of Transition Annex: Bridges Safehouse

- A Case Study of the Conditions Leading to Safe Transition: Bridges Safehouse (See Spanish version)

- A Case Study of the Process of Change: Transitioning Firefly Orphanage (See Spanish version)

- A Case Study of a High-Risk Transition: Lighthouse Children's Village (See Spanish version)

- Residential Care Service Transition

- Care Leaver Support Program MoU Template (Kinnected Myanmar)

- Institution Minimum Standards Assessment Tool (ACC International Relief)

- Partnership Agreement Template (Kinnected Myanmar)

- Partnership Due Diligence Assessment Tool (Rethink Orphanages)